“If a cop is around when an overdose is happening, it is never a safe situation”

P.O.W.E.R. examines reported trend of Vancouver Police interfering in street-level health response

By Molly Beatrice, Tyson Singh Kelsall & P.O.W.E.R. Video by Ryan Sudds, cover photo by Jackie Dives. CW: Police violence, toxic drug deaths, stab wounds, blood.

In interviews with P.O.W.E.R., harm reduction workers corroborate narratives that community members have warned about for years – they allege it is commonly known that Vancouver Police Department (VPD) officers interfere with overdose response.

The impacts of this type of interference can be severe, and in theory, even fatal, particularly during the endless toxic drug emergency.

As Kali Sedgemore states, “Our [harm reduction workers] job is just to intervene in that moment until the – I call them second responders – arrive because we’re the first responders.”

P.O.W.E.R. interviewed Sedgemore, Executive Director of Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War (CPDDW) and lead coordinator of Vancouver’s overnight overdose prevention site (OPS), and Hamish Ballantyne, a community organizer and longtime harm reduction worker.

Both Sedgemore and Ballantyne describe ways in which police can make overdose response more difficult – or directly interfere with overdose response.

Ballantyne describes an incident where cops refused to allow harm reduction workers and community members to respond to an overdose. In his interview with P.O.W.E.R., Ballatyne identifies that he has had several encounters with VPD interfering in his overdose response.

During Sedgemore’s time at the overnight OPS, they encountered multiple incidents of VPD blocking them from responding to people overdosing.

Sedgemore and Ballantyne’s interviews are just a few examples of a broader pattern of law enforcement practices, which interfere in overdose response.

Both share accounts that are similar to reports to P.O.W.E.R. from other Downtown Eastside (DTES) residents.

Cops are not only unequipped to perform accurate overdose response, but they can actively make overdose response unsafe both for the community members responding and for the person that is overdosing, according to interviews and reports to P.O.W.E.R.

The VPD create exclusion zones that prevent community members from accessing someone in medical distress. Sedgemore describes ways VPD officers can restricts access – through physically blocking, use of police tape, or even VPD cruisers.

Ballantyne points to a recent incident in August of 2024 when a VPD officer interfered after Ballantyne had already began responding to an overdose on the street. He details the cop skipping first aid assessment and immediately beginning compressions even though the person overdosing still had a heartbeat – a choice that puts the person overdosing at risk.

In this case, the officers intervention caused harm both by adding an obstacle for the first responder and providing inaccurate first aid to the person in medical distress. Ballantyne stresses the process taught in first aid courses, outlining the thorough process of assessment – and how to respond to the emergency accordingly.

Ballantyne reflects on the way that responding to an overdose has changed given the increasingly contaminated drug supply – a supply that continues to shift to evade changing methods of law enforcement crackdowns.

“There is zero trust from cops in people who aren’t in uniform to provide life saving care,” adds Ballatyne.

This trend extends beyond overdose response. Ballantyne recounts his experiences with VPD restricting his access to responding to other medical emergencies as well – in this instance he was unable to attend to a person suffering from severe stab wounds.

In 2023, the VPD similarly, allegedly interfered with first aid and healthcare worker response after one of their officers drove into Dennis Hunter on East Hastings street.

The police are the enforcement arm of our carceral system, and in any health emergency they have competing priorities, including the possibility of criminalizing someone during a medical emergency. As it stands, VPD officers have both the legal authority and weaponry to restrict life-saving measures.

Ballantyne adds that law enforcement intereference practices are “expressive of an antagonism with people who live in community”.

The DTES is an adaptive, resilient community surviving intersecting policy-driven crises – housing, a toxic drug supply, climate change, for starters. Reports to P.O.W.E.R. indicate that cops nevertheless interfere in community built safety initiatives, and make it more difficult for people to keep each other safe in the face of organized abandonment.

P.O.W.E.R. researcher Jon Braithwaite, who previously helped run a different OPS, shares a similar sentiment.

“Cops…would park right in front of our facility. And what that does is discourages clients from actually coming in the facility. Once they see the police, they go the other way, that’s just the way it is,” said Braithwaite.

Braithwaite eventually placed temporary signs outside the OPS that stated “for every minute you park here, people are dying” to discourage police from parking so close.

“It can be devastating” Sedgemore stresses how essential it is to be able to access someone when they are in medical distress– being able to respond immediately is essential.

In addition to restricting the community members from responding to an overdose, Sedgemore describes some ways in which VPD officers can make a responder feel unsafe to respond. Sedgemore describes an incident in Mount Pleasant where they responded to an overdose while being openly harassed by a group of VPD officers and did not feel safe until paramedics arrived on scene.

The VPD have long taken controversial – if not outright violent – positions around the toxic drug public health emergency and harm reduction.

In 2016, it was then-VPD spokesperson Brian Montague who helped spread the false claim that touching fentanyl could lead to exposure and subsequent overdose. It was for this reason that the VPD had refused to carry naloxone. Eventually, it was for this same reason that they changed their mind – they were scared their officers would be exposed to fentanyl by touch and (impossibly) overdose, so they began to carry naloxone kits to save themselves from a police-driven myth.

It is VPD officers who have conducted thousands of drug seizures during a public health emergency, despite established research showing seizures, particularly fentanyl seizures and raids, contribute to increased overdose risk across the regions in which they are conducted.

The VPD have also been known, as Braithwaite described, to linger outside of overdose prevention sites, which can discourage attendance in a life-saving intervention.

“It shows that cops don’t give a shit and they’d rather let drug users die,” says Sedgemore.

Ballantyne concludes, “The only really good way that a cop can help you respond to an overdose is by not helping, by not being there”

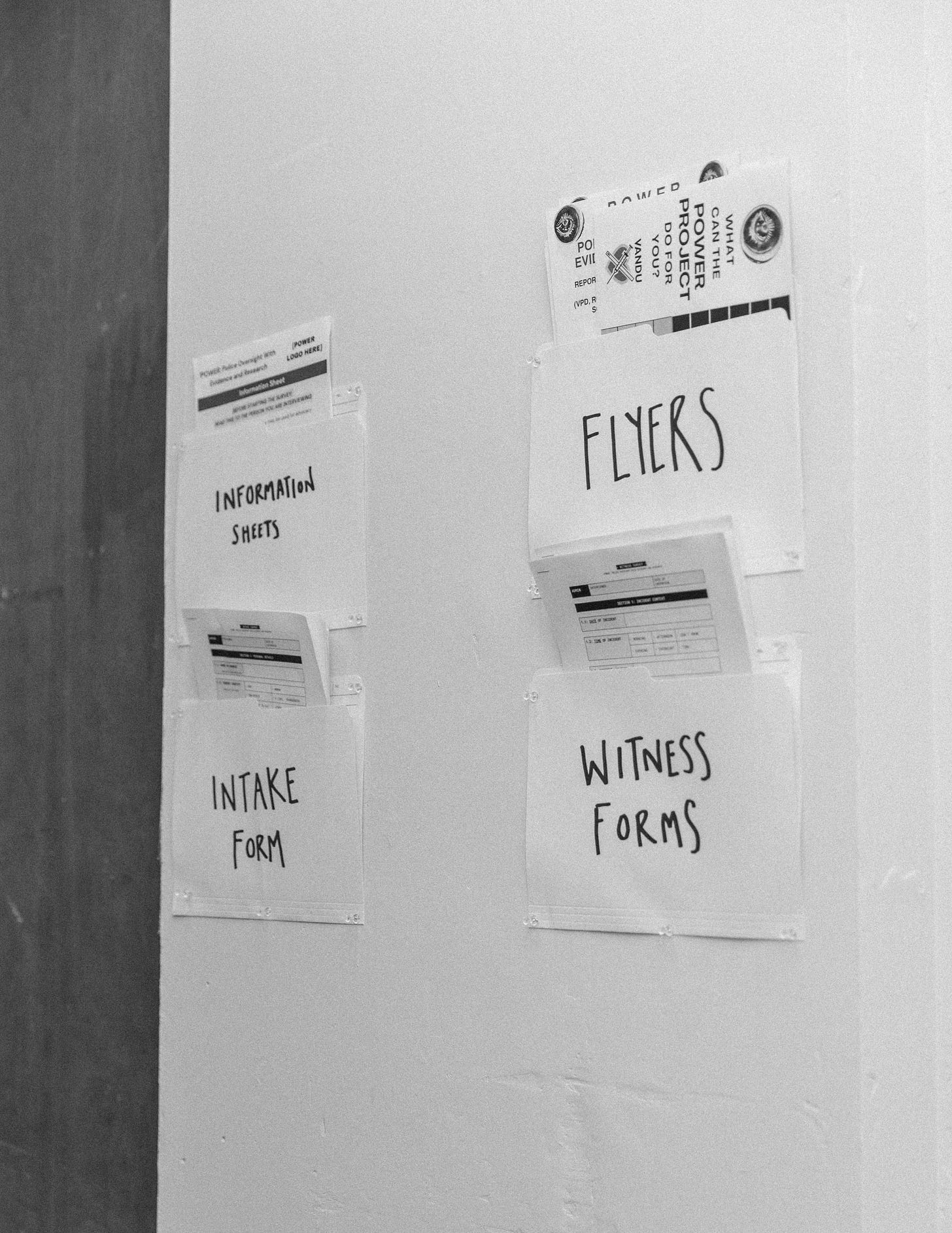

Want to report an encounter where the police have interfered in an overdose or other healthcare response? Email: power@vandu.org

BACKGROUND:

Risk of illicit drug toxicity death in different regions of British Columbia

Vancouver Police Drug Seizures Increased After “Decrim”

His Video Sparked a Probe into Police Misconduct. Then the Traffic Stops Started

Harm reduction activists have our trust; without their activism, we would all be left to die