truth-telling

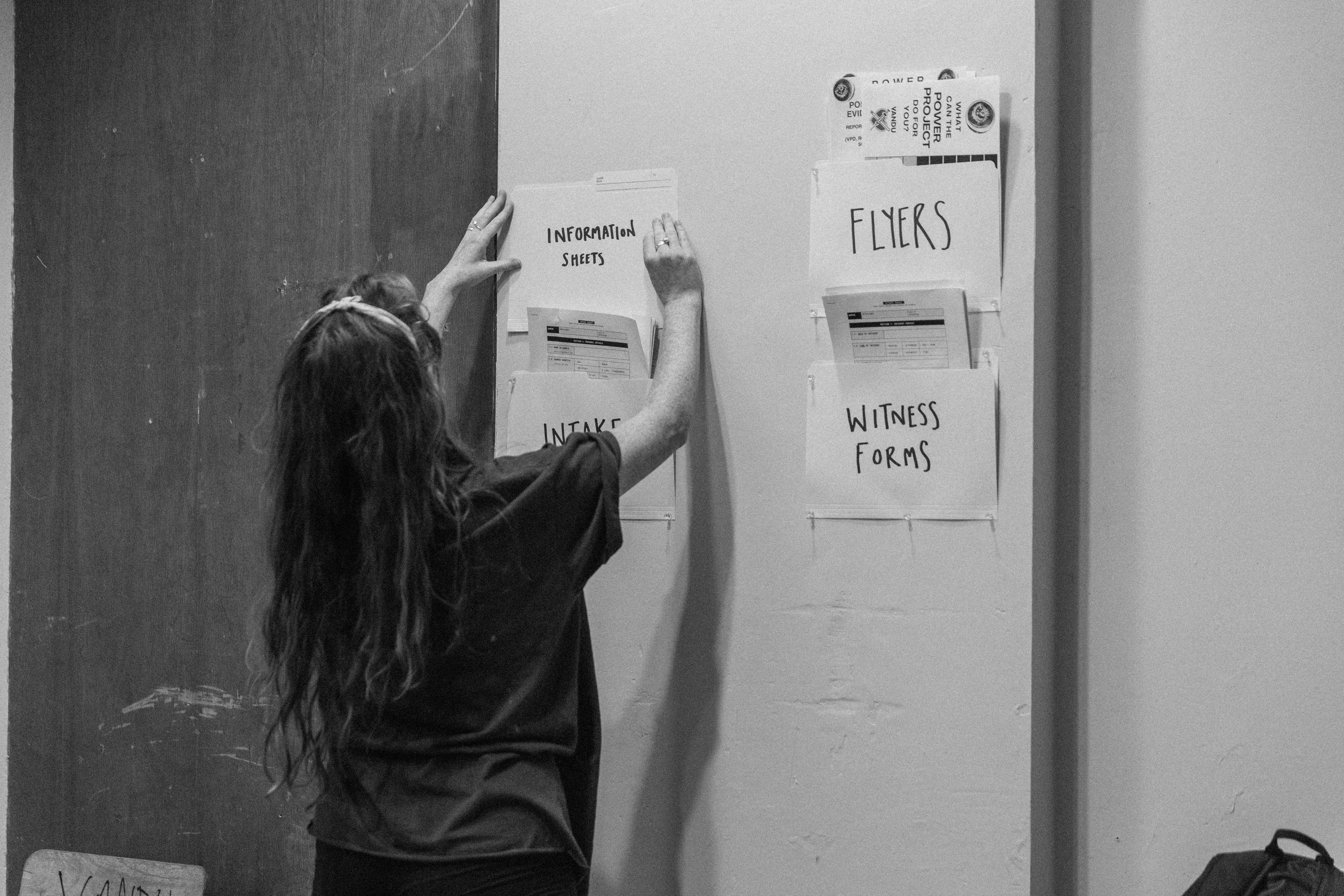

early days of a police oversight project through a media fog

by Tyson Singh & Molly Beatrice

Photos by Jackie Dives

A stranger walks into 380 East Hastings. Their shirt features the insignia of a local activist group. It is possibly the first time it has been worn. The Stranger wonders where in the building our meeting is being held.

We are not yet sure how to situate the Stranger. Are they a researcher? A media representative? An undercover cop? Do they genuinely hold a desire to share what they have endured from the police in this city?

To this day, if this Stranger were a journalist, many would consider them to be a potential mediator of objectivity, in a valuable position to seek truth. But if we imagine the Stranger as a composite, made-up of dominant perspectives in today’s media cycle, we can safely speculate their narrative would misrepresent our understanding of the story.

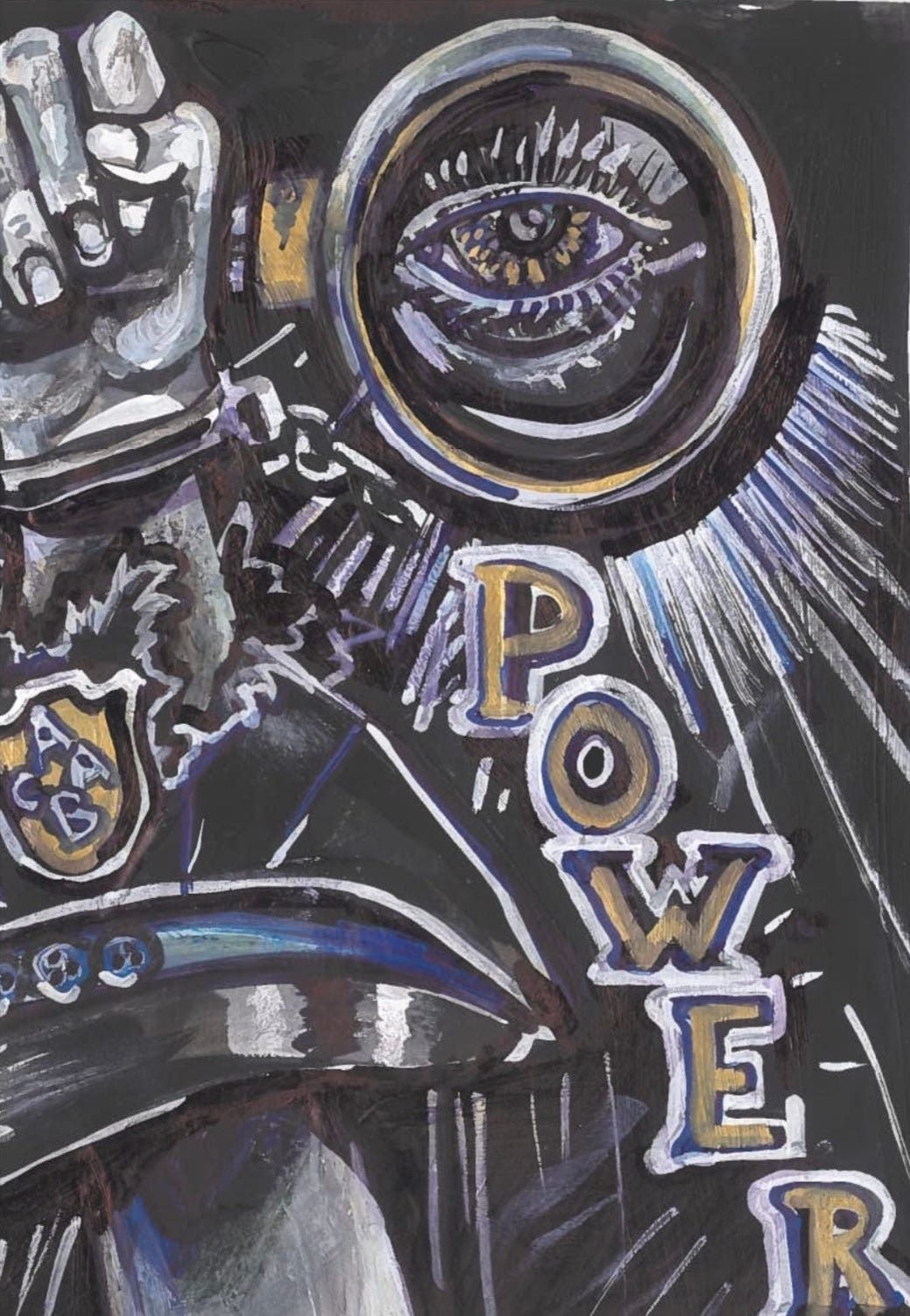

While Police Oversight with Evidence and Research (P.O.W.E.R) is primarily about police accountability, we know that truth-seeking is part of any such process – our mission statement outlines the need to narrow the discursive gap between police-led narratives and the realities of everyday life for those who are most/overpoliced.

For years, decades, since contact, there have been calls to end the violent institution of policing on these lands – it is, after all, the frontline of colonial power and violence, including acting out the local repercussions and our complicity in the international, imperialist drug war.

There have been calls to reform, defund, dismantle, and abolish the Vancouver Police Department. There have been demands for public accountability. There have been attempts and movements to hack apart the roots of social problems that law enforcement weaponize to justify their enormous share of government budgets – solutions, such as the provision of a regulated drug supply, the full decriminalization of substance use and possession, funding adequate and dignified housing, and ensuring income assistance and disability payment rates can support someone’s way out of the constant cycles of criminalization.

But in the past two years, there appears to have been a distinct and visceral rise in funnelling all resources into the spread of a carceral response into managing everything, even while people we know are displaced and never seen again. All while the unregulated, illicit drug market spreads endless harm and violence throughout many of the city’s neighbourhoods.

A number of media publications and reporters have played a role in obscuring these daily realities.

To discuss honestly how the unregulated drug emergency has been misrepresented by some media outlets, examining the texts of opinion columnists from the National Post, a paper stewing in decades of denialism, or their British equivalent, is not worth our resources. To be so evil makes it clear – these writers have picked a side: compel people to pass away from a preventable death, and ensure those who benefit from our societal status quo continue to do so.

It is the insidious, papercut mistruths, and other service to power that are the larger obstacles to a unified understanding of our emergencies.

These narratives dress themselves up. In downtown Vancouver alone, reporters have ‘disguised’ themselves as who they imagine to buy drugs, by wearing a t-shirt and fitting a cigarette behind their ear. Others have repeatedly made unfounded claims outside their realm of expertise to conflate unregulated drug treatment beds with a solution to the overdose crisis – even though no number of beds can regulate a contaminated drug supply. Reporters have uncritically printed claims that Suboxone® is considered a gold-standard treatment, while the pharmaceutical company behind the local brand of the medication settles alleged felony charges, and has allegedly peddled false information in other regions. Many in the media seem unwilling or unable to critically reflect on their own use of the colloquial pejorative ‘addiction,’ despite its removal from care and medical lexicon, and reclamation by those who identify with it.

Displacement and carceral punishment represented in mainstream media at a glance would suggest that the state is capable of violent events, and may occasionally identify a trend of violence, but only if extreme enough to disrupt the veil of copaganda.

What is concealed is that the violence of displacement happens every single day, at every hour, and invisibilizing poverty is full time work for colonial cities at the intersection of the housing and toxic drug crises. The dominant media narratives are unable to catch the reality of daily state violence, and in the same breath are unable to capture its daily resistance. The failure to represent every day community care, mutual aid, harm reduction is a step in further sensationalizing and alienating those most vulnerable to violence.

In her speech Conscience of Words, Susan Sontag separated opinion writing from a more direct contributor to misinformation as opinion-mongering, “There is something vulgar about public dissemination of opinions on matters about which one does not have extensive first-hand knowledge. If I speak of what I do not know, or know hastily, this is mere opinion-mongering.”

We are wary of the struggles in local media: the endless job cuts, the intensifying corporatization of media ownership, the competition for scarce media revenue, and the nature of columnists and daily news reporters morphing into one role employed by the same person. As Michelle Cyca wrote recently in the The Walrus:

[M]edia outlets grapple with these complex intersecting challenges, they are also racing to be the first to publish stories that will reach as many people as possible; striving for virality is a survival tactic, particularly when you rely on digital advertising revenue.

Still, when it comes to the emergencies of the toxic drug crisis and forced displacement, inaccurately scapegoating those at highest risk of serious and fatal harm only feeds into the violence those working in media may intend to expose. This can act as a form of public relations for the apparatus of power that generates and then manages the violence at the centre of these narratives.

As Cyca concludes, an end result of vapid attention seeking “might be losing what credibility and integrity” legacy media publications have left.

The false balance of two-sided stories

If we treat the Stranger like an objective blank slate of dominant media perspectives, they would begin with a deficit in striving to capture reality (and in their relation to it). For starters, the Stranger is struggling to find our regular meeting place, is unsure what will occur there, and does not know who the group is composed of.

Sontag continued, “the job of the writer is to make it harder to believe the mental despoilers. The job of the writer is to make us see the world as it is, full of many different claims and parts and experiences.”

“It is the job of the writer to depict the realities: the foul realities, the realities of rapture.”

But how could the Stranger accurately report on the realities if they do not comprehend the basics of the operation, the various formal and informal democracies embedded in the community space, the words and colloquialism we use, the feeling of the police officer’s threat or worse?

How can the story be accurate without a century of state violence haunting each word?

James Baldwin once described perspective as a “system of reality.” For Baldwin, this broke down the difference in one's response to a story, depending on “where you find yourself in the world, what your sense of reality is, what your system of reality is.”

“That is, it depends on assumptions which we hold so deeply so as to be scarcely aware of them.”

To hide behind passive descriptors or to give undeserved weight to an oppositional voice solely to find a second side of a story creates the spaces for false information to creep in, to breathe oxygen and to spread, generally at the behest of power and against those who do not benefit from it.

In the Columbia Journalism Review, Wesley Lowery writes “when the weight of the evidence is clear, it is wrong to conceal the truth.”

“Justified as ‘objectivity,’ they are in fact it's distortion.”

Mohammed El-Kurd in The Nation, reminds journalists that this tension is not even about moral courage, “It’s about doing our jobs. If our job is to report the truth, we must report the truth.”

For example, media personnel do not have to dignify police charts that are plainly incoherent, nor give them space to discuss prohibitionist policies without contextualizing their conflict of fiscal interest, nor take seriously the commissioned reports that the politicized force funds, nor the ones that former members help write (and later weaponize).

Police public relations dishonesty and oversimplification toward the violence of displacement likewise does not deserve oxygen, especially as the VPD actively met violence on the public.

Not all sides of stories are always equal in value, and not every story has multiple sides that are rooted in honesty or removed enough from the constraints of profit-seeking to be given equal balance.

Last week, for instance, the sex worker rights-based group Supporting Women’s Alternatives Network (SWAN) Vancouver called for better media coverage, including that reporters question police narratives surrounding enforcing sex work-related criminalization. While The Bind has critiqued media representations of police drug raids in BC.

Violence deserves an honest portrayal, or as Cyca warned, many of us will continue to turn our back to the traditional media landscape, leading to further decentralization of the truth and fractured realities. But it makes us less directly complicit than engaging in dishonest representation.

Our own bias is rooted in the goal of ending the forms of the state-driven violence we have described – and part of this is challenging and speaking truth to power – a role we understand to similarly be part of a healthy media landscape.

Further reading:

Gina Starblanket: Complex Accountabilities: Deconstructing “the Community” and Engaging Indigenous Feminist Research Methods

New York Times: A Reckoning Over Objectivity, Led by Black Journalists

International Journal of Drug Policy: Decriminalization or police mission creep? Critical appraisal of law enforcement involvement in British Columbia, Canada's decriminalization framework

Pivot Legal: Police Violence in the DTES

Drug Data Decoded: Without their activism, we would all be left to die